FEATURE/Connecting with underground society: Author tells stories of migrant workers

02/12/2024 03:23 PM

Taiwan began to employ larger numbers of migrant workers as part of its labor force more than 30 years ago. Over the years, although these workers have become increasingly indispensable, the general public's understanding of the community remains limited.

(Full text of the story is now in CNA English news archive. To view the full story, you will need to be a subscribed member of the CNA archive. To subscribe, please read here.)

More in FEATURE

![Hualien flood leaves Taiwan grappling with disaster response gaps]() Hualien flood leaves Taiwan grappling with disaster response gapsOn Sept. 23, a historic downpour caused the Matai'an Barrier Lake in Hualien to burst its banks, sending 60 million tons of water and debris through Guangfu Township and killing at least 19 people.10/16/2025 05:02 PM

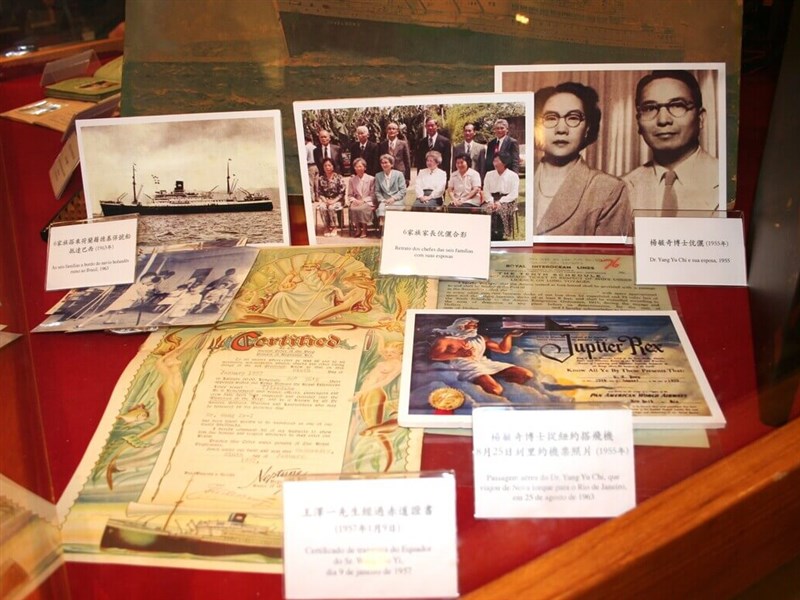

Hualien flood leaves Taiwan grappling with disaster response gapsOn Sept. 23, a historic downpour caused the Matai'an Barrier Lake in Hualien to burst its banks, sending 60 million tons of water and debris through Guangfu Township and killing at least 19 people.10/16/2025 05:02 PM![Fala Formosa! Taiwanese expats to Brazil carve 7 decades of immigrant stories]() Fala Formosa! Taiwanese expats to Brazil carve 7 decades of immigrant storiesSão Paulo is not typically thought of as a hotspot for Taiwanese restaurants and Boba tea shops, much less places that attract long lines of patrons.10/03/2025 04:08 PM

Fala Formosa! Taiwanese expats to Brazil carve 7 decades of immigrant storiesSão Paulo is not typically thought of as a hotspot for Taiwanese restaurants and Boba tea shops, much less places that attract long lines of patrons.10/03/2025 04:08 PM![A recipe for daily life: Taipei's homeless struggle to find food]() A recipe for daily life: Taipei's homeless struggle to find foodUnlike most Taipei residents, Chang Yun-hsiang's (張雲翔) first view in the morning is the open sky. His alarm is the sound of increasing vehicular and pedestrian traffic near Taipei Main Station, where he sleeps on the street a block away.09/20/2025 03:34 PM

A recipe for daily life: Taipei's homeless struggle to find foodUnlike most Taipei residents, Chang Yun-hsiang's (張雲翔) first view in the morning is the open sky. His alarm is the sound of increasing vehicular and pedestrian traffic near Taipei Main Station, where he sleeps on the street a block away.09/20/2025 03:34 PM

Latest

- Culture

Taiwan testing new path to U.S. universities without TOEFL

11/17/2025 09:25 PM - Politics

Taiwan names new ambassador to Palau

11/17/2025 08:56 PM - Sports

Saitama Seibu Lions earn right to negotiate with CPBL's Lin An-ko

11/17/2025 08:47 PM - Culture

Doctor, author Chen Yao-chang dies at 76

11/17/2025 08:41 PM - Politics

KMT lawmakers urge president to pardon mother in 'mercy killing' case

11/17/2025 07:34 PM