FEATURE/Motherhood at a cost: The struggles of pregnant migrant workers in Taiwan

By Sean Lin, CNA Staff reporter

[Editor's Note: This is part two of a two-part series examining the health and work challenges facing both legal and undocumented migrant workers in Taiwan who are pregnant or raising children, as well as the health issues affecting their children.]

When an Indonesian woman named Ratih got pregnant last year, she figured she would continue on her job at a New Taipei manufacturer before taking maternity leave, as is provided by law.

Instead, when she was five months pregnant, her employer and employment broker told her they decided it would be in her best interest to return to Indonesia to give birth, even though her supervisor agreed that she take maternity leave.

They eventually succeeded in pressuring Ratih to quit, but the official paperwork delivered to the local labor department said she had "resigned willingly," undermining her legal position.

The case eventually went to arbitration, and the factory agreed to pay Ratih severance. Still, her life was upended. She was forced to move to a migrant worker shelter run by the Serve the People Association (SPA) in Taoyuan, and continues to live there after having given birth.

Employer coercion

Ratih's story is typical of the pressures faced by pregnant migrant workers, and the difficulties they have in bucking a system that is clearly not on their side, even if the law often is.

Both the Gender Equality in Employment Act and the Labor Standards Act clearly state pregnant employees like Ratih cannot be fired and that they are entitled to eight weeks of maternity leave, but the clause is not easily enforced, helping perpetuate the discrimination these women face.

"If they were Taiwanese, they would have no trouble getting maternity leave," said Lina, one of the shelter's coordinators who handles a wide range of responsibilities.

With migrant workers, employers and brokers try to steer clear of legal liability by pushing them in the mid-stages of their pregnancy to reach a "mutual agreement" to dissolve their contracts, Lina said.

Most migrant workers agree to this kind of deal because they do not want the "trouble" that would follow if they chose otherwise, particularly trouble with their manpower brokers, she said.

High termination rate for pregnant migrants

Another Indonesian woman named Seri, who worked at a long-term care facility, faced the same pressures when she became pregnant, which was why she ended up staying at the same shelter as Ratih.

"As my job required me to take care of elderly people and sometimes lift them, my employer decided when I was four months pregnant to let me go because it was simply too risky for me," Seri said.

According to Lina, Seri's case illustrates how caregivers, especially those working alone in private homes, may be the most vulnerable of any group of migrants when they become pregnant.

Because they are typically responsible for a single infirm individual, their contracts are almost always terminated once their employers view them as unfit for the job, Lina said.

Regardless of the type of work being done by pregnant migrant workers, losing their jobs illegally is a phenomenon that is only growing more common in Taiwan.

In 2022, the Control Yuan, Taiwan's top government watchdog, censured the MOL because the percentage of pregnant migrant workers who had to dissolve their contracts rose sharply to 66.1 percent in 2021 from about 40 percent in 2019.

It also found that of the 13,521 migrant workers who gave birth in Taiwan before returning to their home countries from 2018 to 2021, 8,010 had to first terminate their employment contracts.

That practice violates the United Nations' Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which Taiwan incorporated into its domestic law in 2012.

The convention prohibits the dismissal of female workers on the grounds of pregnancy or maternity leave, the Control Yuan said.

Real-life consequences

Some may argue that the situation is not so serious, given that pregnancy is one of the few circumstances under which migrant workers can seek a new employer before their existing contract expires, provided it is terminated through mutual agreement with the employer.

Pregnant migrant workers are granted a leeway period of up to 180 days after childbirth to find a new job, after which they must return to their home country if they remain unemployed.

Yet having their contracts dissolved puts the workers in a real-life bind, Lina said, depriving them of a stable place to live and leaving them vulnerable to exorbitant "brokerage fees" for securing a new contract, even though such fees are prohibited by law.

Strong enough response?

To address the struggles of pregnant migrant workers, the Ministry of Labor (MOL) spent the better part of 2024 compiling the "Guidelines to Protect the Rights of Female Foreign Workers and Their Children."

In May 2024, it said it would extend childbirth subsidies to migrant domestic caregivers by including such a policy in the guidelines, which are reserved for workers covered by the Labor Standards Act.

The plan sparked a backlash among the Taiwanese public, however, and was eventually scrapped.

When the guidelines were finally released on Jan. 6, 2025, they came in the form of a compilation of existing rules and resources, including, for example, where migrant workers could read about birth control and get contraceptive pills.

They also outlined the types of leave pregnant or new mothers are entitled to, and even explicitly said that employers must not use pregnancy as a reason for dismissing an employee.

Yet the guidelines did not provide for any form of enforcement of the rules or punishment of offenders.

Hsiao Yicai (蕭以采), director of the SPA shelter, was somewhat skeptical about how effective a compilation of existing rules would be when helping pregnant migrant workers.

"The real problem is that the measures are difficult to enforce because many pregnant migrant workers do not know about them, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation.

"Or maybe they do but are afraid to stand up for their rights after being threatened by their employment agencies," Hsiao said.

Enditem/ls

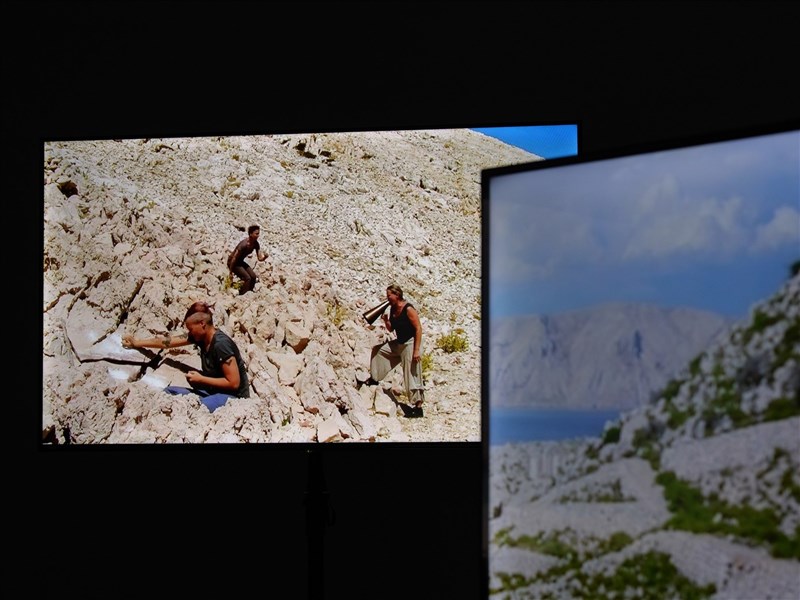

![From isolation to reflection: Green Island Biennial looks at islands of repression]() From isolation to reflection: Green Island Biennial looks at islands of repressionAfter the first group of political prisoners was sent to Green Island in May 1951, several thousand more followed over the next three decades, incarcerated on a small outpost off Taiwan's southeastern coast.08/05/2025 03:08 PM

From isolation to reflection: Green Island Biennial looks at islands of repressionAfter the first group of political prisoners was sent to Green Island in May 1951, several thousand more followed over the next three decades, incarcerated on a small outpost off Taiwan's southeastern coast.08/05/2025 03:08 PM![Houston, we have a solution: Taiwan space startup adjusts satellite attitudes]() Houston, we have a solution: Taiwan space startup adjusts satellite attitudesIt is 2004, and a couple of giant globes roll past a fatigued Will Smith in a self-driving car in the Hollywood blockbuster sci-fi film "I, Robot."08/03/2025 03:14 PM

Houston, we have a solution: Taiwan space startup adjusts satellite attitudesIt is 2004, and a couple of giant globes roll past a fatigued Will Smith in a self-driving car in the Hollywood blockbuster sci-fi film "I, Robot."08/03/2025 03:14 PM![Ponpon does polka: Taiwanese jazz musician whistles, scats her way onto US news]() Ponpon does polka: Taiwanese jazz musician whistles, scats her way onto US news"Originally from Taiwan and now one of California's rising young jazz artists, here is Ponpon Chen and her quintet," declared the announcer of American news program World News Now (WNN) at the conclusion of a May 9 broadcast as the credits rolled.07/21/2025 06:52 PM

Ponpon does polka: Taiwanese jazz musician whistles, scats her way onto US news"Originally from Taiwan and now one of California's rising young jazz artists, here is Ponpon Chen and her quintet," declared the announcer of American news program World News Now (WNN) at the conclusion of a May 9 broadcast as the credits rolled.07/21/2025 06:52 PM

- Politics

KMT Legislator Lo Chih-chiang joins race for party chair

08/25/2025 09:37 PM - Sports

Team Taiwan names coaches for 2026 World Baseball Classic

08/25/2025 09:31 PM - Society

Chunghwa Post suspends small parcel services to U.S. due to tariffs

08/25/2025 08:37 PM - Cross-Strait

Taiwan's Coast Guard shadows trespassing Chinese ships off Kinmen

08/25/2025 07:38 PM - Business

NDC calls for deeper Taiwan-Japan collaboration on innovation

08/25/2025 07:30 PM